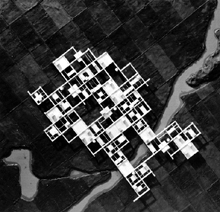

Study of the connection of elements on the site

Study of the connection of elements on the site25 February 2011

Daily Routine

Using the daily rountine as a guide, program elements are separated into two main areas. Observing that the groups spend half the day in the activity rooms and half the day in the garden/market/kitchen, the program is grouped as such and placed in oppostition. The transition between the elements happens mid-day during lunch, therefore the main dining/gathering space acts as the connector.

Studio Culture Policy

School of Architecture and Design

1855 Broadway New York, NY

10023 7692

Old Westbury / Manhattan

February 23, 2011

Studio Culture Policy

Architecture is a field of study that requires tremendous passion and dedication.

Professors expect a great deal, the workload can be daunting, and the range of skills and

abilities one is expected to master is immense. Studio courses are particularly demanding,

which is why they need to be assessed on an ongoing basis. According to the AIAS

(American Institute of Architecture Students) Studio Culture Summit Report (2004),

studio-based education has been highly effective at facilitating life-long learning, creative

expression, self-discovery, and interdisciplinary research. It aims to foster healthy and

productive competition, effective mentoring, a strong sense of community, critical

thinking, and self-reliance. By the same token, it can also lead to rivalry and excessive

competitiveness; it can perpetuate a climate of insularity; it can stifle innovation. The

studio experience tends to reward “star” power (i.e., individualism over collaboration)

and has the potential to allow arbitrary or ungrounded instructor criticisms to go

unchallenged.1

How do you remedy the problems of studio-based architectural education without

also compromising the many benefits it affords? The AIAS’ Studio Culture Summit

Report, the Second AIAS Task Force on Studio Culture (2008), and the National

Architectural Accrediting Board’s (NAAB) Conditions of Accreditation provide us with a

number of clues. The AIAS’ recommendations include acknowledging that change is

already occurring (i.e., that studio-based education is always evolving); developing a

code of best practices; awarding effective pedagogy; improving communication and

coordination between faculty; fostering dialogue, participation, and personal

responsibility.2 NAAB, meanwhile, emphasizes the importance of creating a “positive

and respectful learning environment through the encouragement of the fundamental

values of optimism, respect, sharing, engagement, and innovation between and among the

members of its faculty, student body, administration, and staff. The school should

encourage students and faculty to appreciate these values as guiding principles of

professional conduct throughout their careers.” Every accredited school of architecture

must adopt “a written studio culture policy with a plan for its implementation and

1 Clark Kellogg and the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS), The Studio Culture Summit

Report (2004): 10-11. Available online at http://www.aias.org/website/download.asp?id=313

2 Ibid., 12.

maintenance and provide evidence of abiding by that policy. The plan should specifically

address issues of time management on the part of both the faculty and students.”3

What is NYIT’s studio culture policy? What, more specifically, do we mean by

this term? Here at NYIT, we interpret studio culture comprehensively and holistically. It

is not limited to studio courses, but extends to all aspects of our academic community.

Throughout our curriculum, we especially emphasize good citizenship, which for us

means being responsible for one’s actions. It means practicing mutual tolerance, respect,

and accountability. It means maintaining community and trust, where healthy competition

can thrive. At NYIT, we have a flexible admissions policy, which allows us to attract

students who hail from a range of academic and professional backgrounds. We occupy

two campuses, one in Long Island and a second in Manhattan, which has made us

extremely diverse, ethnically, socially, intellectually, and culturally. We are primarily a

commuter-based school, which means we attract individuals who are independent and

motivated, rooted in their communities, and acutely aware of the importance of timemanagement.

Our studio spaces are not always open on a twenty-four hour basis, which

has forced our students to become more organized. Our graduates are known for their

entrepreneurialism, professionalism, leadership skills, and design and technical abilities,

and we make every effort to nurture these values in studio.

A number of institutions, individuals, and organizations play a vital role in

defining and managing our academic community. This list includes the AIAS, the School

of Architecture and Design’s (SoAD) Curriculum and Technology Committees, NYIT’s

Office of Campus Life, the SoAD’s dean and campus chairs, the AIAS faculty advisors,

the AIAS national leadership, the ACSA, and the Student Government Association

(SGA). Of the organizations just mentioned, the AIAS’ role is especially important, as it

is one of the collateral organizations that comprises NAAB and as such participates in

evaluating accredited programs such as ours. At NYIT, our local AIAS chapters have

acted as effective conduits for voicing student needs and concerns. They facilitate

meetings between faculty, administration, and staff. They give students a collective

identity and holds them accountable for their conduct. They outline areas needing

improvement in our school. They partner with the faculty and administration in reevaluating

and revising our Studio Culture policy on an annual basis. They participate in

faculty committees and curriculum deliberations. They play an active role nationally in

AIAS governance.

What are the highlights of NYIT’s studio culture? We have a long-standing

tradition of encouraging design-build initiatives, which means that our students are wellequipped

to work collaboratively across disciplines. Our program boasts a number of

highly-regarded study abroad programs, which expose students to cultures and traditions

from around the world. (In recent years, studios have been conducted in Italy, The

Netherlands, Germany, China, and Egypt.) Students can expect an intimate classroom

experience taught by dedicated and accomplished professionals. Studio coordinators

work closely with faculty from our history/theory, technology, and liberal arts divisions

in coordinating their respective syllabi and course objectives. Our school boasts a twosemester

thesis sequence that allows students to pursue individualized themes and issues

with leading designers and architects. We also regularly organize events that allow

students and faculty to share ideas with one another, as well as with the NYIT community

at large.

3 To view NAAB’s Conditions of Accreditation, visit

http://www.naab.org/accreditation/2004_Conditions_2.aspx.

What are some of the resources and amenities that every NYIT student can expect

in our school? Here is a partial list, drafted by the AIAS in collaboration with the SoAD’s

faculty and administration:

• Students can always expect well-maintained classrooms, studio spaces, computer labs,

and fabrication labs. They can expect that all hardware and software they use will be

current and properly maintained, and that all classrooms will be outfitted with appropriate

media – whether it be projectors, computers, or monitors. It will also maintain plotters

and other print-related media.

• Students can also expect that their education will always be professionally relevant. They

will be prepared for portions of the ARE (Architectural Registration Examination) by the

time of graduation and will always be taught by leading scholars, researchers, and

professionals. Every effort is made to assist students with job placement, particularly

through the resources of NYIT’s Career Services Office, as well as to keep them

informed about IDP (Intern Development Program) and other opportunities relevant to

practicing architects.

• The School of Architecture and Design pledges to do everything it can to maintain an

environment that is tolerant and respectful vis-à-vis its diverse students and faculty, and

which is safe for all individuals and their property.

• The School of Architecture and Design will continue to teach professional excellence, not

only by imparting basic design and critical thinking skills, but also by emphasizing time

management, collaboration, and professionalism. We do not believe that “pulling allnighters”

needs to be a part of architectural education. On the contrary, our view is that

the best professional is the one who manages his or her time best, who is well-read and

well-rounded, and can connect her or his professional training to the concerns of the

broader world at large.

On a final note, it needs to be stressed that our goal at NYIT is to educate “the whole

architect,” and to that end one of our primary objects is to assist students with figuring out how to

get the most out of their education, not just intellectually and artistically, but also socially and

emotionally. Along these lines, if you have suggestions about how we can improve the quality of

your experience at the SoAD, or in studio more specifically, we would love to hear from you. We

encourage you to get involved with your local AIAS chapter. We urge you to communicate your

concerns to your campus chair or dean.

To obtain assistance with time-management issues, feel free to speak to NYIT’s Office

of Academic Life and Retention Services, your department chair, or faculty instructor. For more

information about studio culture in general, be sure to review the literature on this topic available

on the AIAS Website: http://www.aias.org/website/article.asp?id=78.

1855 Broadway New York, NY

10023 7692

Old Westbury / Manhattan

February 23, 2011

Studio Culture Policy

Architecture is a field of study that requires tremendous passion and dedication.

Professors expect a great deal, the workload can be daunting, and the range of skills and

abilities one is expected to master is immense. Studio courses are particularly demanding,

which is why they need to be assessed on an ongoing basis. According to the AIAS

(American Institute of Architecture Students) Studio Culture Summit Report (2004),

studio-based education has been highly effective at facilitating life-long learning, creative

expression, self-discovery, and interdisciplinary research. It aims to foster healthy and

productive competition, effective mentoring, a strong sense of community, critical

thinking, and self-reliance. By the same token, it can also lead to rivalry and excessive

competitiveness; it can perpetuate a climate of insularity; it can stifle innovation. The

studio experience tends to reward “star” power (i.e., individualism over collaboration)

and has the potential to allow arbitrary or ungrounded instructor criticisms to go

unchallenged.1

How do you remedy the problems of studio-based architectural education without

also compromising the many benefits it affords? The AIAS’ Studio Culture Summit

Report, the Second AIAS Task Force on Studio Culture (2008), and the National

Architectural Accrediting Board’s (NAAB) Conditions of Accreditation provide us with a

number of clues. The AIAS’ recommendations include acknowledging that change is

already occurring (i.e., that studio-based education is always evolving); developing a

code of best practices; awarding effective pedagogy; improving communication and

coordination between faculty; fostering dialogue, participation, and personal

responsibility.2 NAAB, meanwhile, emphasizes the importance of creating a “positive

and respectful learning environment through the encouragement of the fundamental

values of optimism, respect, sharing, engagement, and innovation between and among the

members of its faculty, student body, administration, and staff. The school should

encourage students and faculty to appreciate these values as guiding principles of

professional conduct throughout their careers.” Every accredited school of architecture

must adopt “a written studio culture policy with a plan for its implementation and

1 Clark Kellogg and the American Institute of Architecture Students (AIAS), The Studio Culture Summit

Report (2004): 10-11. Available online at http://www.aias.org/website/download.asp?id=313

2 Ibid., 12.

maintenance and provide evidence of abiding by that policy. The plan should specifically

address issues of time management on the part of both the faculty and students.”3

What is NYIT’s studio culture policy? What, more specifically, do we mean by

this term? Here at NYIT, we interpret studio culture comprehensively and holistically. It

is not limited to studio courses, but extends to all aspects of our academic community.

Throughout our curriculum, we especially emphasize good citizenship, which for us

means being responsible for one’s actions. It means practicing mutual tolerance, respect,

and accountability. It means maintaining community and trust, where healthy competition

can thrive. At NYIT, we have a flexible admissions policy, which allows us to attract

students who hail from a range of academic and professional backgrounds. We occupy

two campuses, one in Long Island and a second in Manhattan, which has made us

extremely diverse, ethnically, socially, intellectually, and culturally. We are primarily a

commuter-based school, which means we attract individuals who are independent and

motivated, rooted in their communities, and acutely aware of the importance of timemanagement.

Our studio spaces are not always open on a twenty-four hour basis, which

has forced our students to become more organized. Our graduates are known for their

entrepreneurialism, professionalism, leadership skills, and design and technical abilities,

and we make every effort to nurture these values in studio.

A number of institutions, individuals, and organizations play a vital role in

defining and managing our academic community. This list includes the AIAS, the School

of Architecture and Design’s (SoAD) Curriculum and Technology Committees, NYIT’s

Office of Campus Life, the SoAD’s dean and campus chairs, the AIAS faculty advisors,

the AIAS national leadership, the ACSA, and the Student Government Association

(SGA). Of the organizations just mentioned, the AIAS’ role is especially important, as it

is one of the collateral organizations that comprises NAAB and as such participates in

evaluating accredited programs such as ours. At NYIT, our local AIAS chapters have

acted as effective conduits for voicing student needs and concerns. They facilitate

meetings between faculty, administration, and staff. They give students a collective

identity and holds them accountable for their conduct. They outline areas needing

improvement in our school. They partner with the faculty and administration in reevaluating

and revising our Studio Culture policy on an annual basis. They participate in

faculty committees and curriculum deliberations. They play an active role nationally in

AIAS governance.

What are the highlights of NYIT’s studio culture? We have a long-standing

tradition of encouraging design-build initiatives, which means that our students are wellequipped

to work collaboratively across disciplines. Our program boasts a number of

highly-regarded study abroad programs, which expose students to cultures and traditions

from around the world. (In recent years, studios have been conducted in Italy, The

Netherlands, Germany, China, and Egypt.) Students can expect an intimate classroom

experience taught by dedicated and accomplished professionals. Studio coordinators

work closely with faculty from our history/theory, technology, and liberal arts divisions

in coordinating their respective syllabi and course objectives. Our school boasts a twosemester

thesis sequence that allows students to pursue individualized themes and issues

with leading designers and architects. We also regularly organize events that allow

students and faculty to share ideas with one another, as well as with the NYIT community

at large.

3 To view NAAB’s Conditions of Accreditation, visit

http://www.naab.org/accreditation/2004_Conditions_2.aspx.

What are some of the resources and amenities that every NYIT student can expect

in our school? Here is a partial list, drafted by the AIAS in collaboration with the SoAD’s

faculty and administration:

• Students can always expect well-maintained classrooms, studio spaces, computer labs,

and fabrication labs. They can expect that all hardware and software they use will be

current and properly maintained, and that all classrooms will be outfitted with appropriate

media – whether it be projectors, computers, or monitors. It will also maintain plotters

and other print-related media.

• Students can also expect that their education will always be professionally relevant. They

will be prepared for portions of the ARE (Architectural Registration Examination) by the

time of graduation and will always be taught by leading scholars, researchers, and

professionals. Every effort is made to assist students with job placement, particularly

through the resources of NYIT’s Career Services Office, as well as to keep them

informed about IDP (Intern Development Program) and other opportunities relevant to

practicing architects.

• The School of Architecture and Design pledges to do everything it can to maintain an

environment that is tolerant and respectful vis-à-vis its diverse students and faculty, and

which is safe for all individuals and their property.

• The School of Architecture and Design will continue to teach professional excellence, not

only by imparting basic design and critical thinking skills, but also by emphasizing time

management, collaboration, and professionalism. We do not believe that “pulling allnighters”

needs to be a part of architectural education. On the contrary, our view is that

the best professional is the one who manages his or her time best, who is well-read and

well-rounded, and can connect her or his professional training to the concerns of the

broader world at large.

On a final note, it needs to be stressed that our goal at NYIT is to educate “the whole

architect,” and to that end one of our primary objects is to assist students with figuring out how to

get the most out of their education, not just intellectually and artistically, but also socially and

emotionally. Along these lines, if you have suggestions about how we can improve the quality of

your experience at the SoAD, or in studio more specifically, we would love to hear from you. We

encourage you to get involved with your local AIAS chapter. We urge you to communicate your

concerns to your campus chair or dean.

To obtain assistance with time-management issues, feel free to speak to NYIT’s Office

of Academic Life and Retention Services, your department chair, or faculty instructor. For more

information about studio culture in general, be sure to review the literature on this topic available

on the AIAS Website: http://www.aias.org/website/article.asp?id=78.

23 February 2011

FLW Usonian Housing

21 February 2011

Strip Farming

Strip Farming is a way of alternating crops in rows. This allows the vegetation to follow contours which slows the rate of water run-off. It also creates a fuel efficiency while running equipment and produces less wear on the equipment itself. By planting in rows, it creates a rich soil of organic matter as rotation occurs, and as the soil fertility increases, insects decrease, and produce quality increases.

20 February 2011

Scaling/Farming Transition

18 February 2011

Mike see this

Poster illusion

i dont know if you ever saw these but i just think the idea could be easily be applied to your project in the future since its a good illusion that could be used when it comes to textures and materials for your building

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-f8mGm3pzQ0&feature=topvideos

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMTkttFqKuI&NR=1&feature=fvwp

i dont know if you ever saw these but i just think the idea could be easily be applied to your project in the future since its a good illusion that could be used when it comes to textures and materials for your building

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-f8mGm3pzQ0&feature=topvideos

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BMTkttFqKuI&NR=1&feature=fvwp

16 February 2011

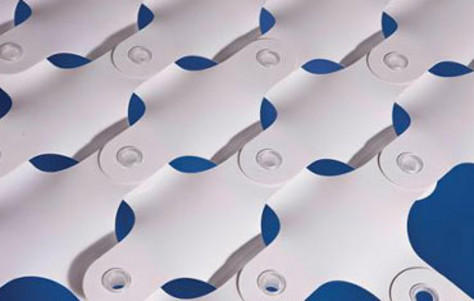

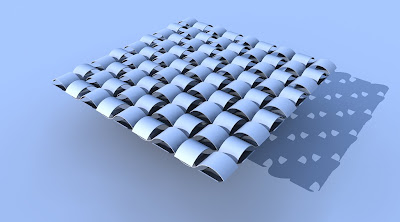

Weave Stitch

15 February 2011

14 February 2011

IDP presentation tomorrow

Hello All,

We are having a big IDP presentation tomorrow, Tuesday the 15th. 12:30 - 2:00. Cafeteria. Two guests will present. The whole IDP, ARE, LICENSURE, TO NCARB explanation.

IMPORTANT AND USEFUL OPPORTUNITY.

The AIAs will have pizza and drinks on hand. Please feel free to forward this note to all of your students.

Thanks,

Bill

Carlos

Two things for you to look at:

MODENA CEMETERY: Modena, Italy

and

The built, the unbuilt, and the unbuildable : in pursuit of architectural meaning

Author

Harbison, Robert.

Publisher:

MIT Press,

Pub date:

1991.

Pages:

192 p. :

ISBN:

0262082047

MODENA CEMETERY: Modena, Italy

and

| Education Hall Library | Copies | Material | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| NA2500 .H37 1991 | 1 | Book | Standard shelving location |

Progress

Had to go back and redo the ramps as there was to much clutter in the other ones and they were too close to program i had to introduce later, now they are placed almost in the middle of the whole structure so that the bridging will have some room to be and everyone gets to experience the spatial qualities of the ramps wether in them or not.

Dont pay much attention to the straight columns I have here they are all uneven for now but will be readjusted later on once I place the upper stands.

more to come.....

09 February 2011

Friday Pin-up

All,

I thought yesterday was mostly productive and you did receive some good comments. I’m glad we took a breather from the regularly scheduled program.

The business for Friday will be simple. Pin-up and present your current info only. We all know in general what’s going on in each others project. I want to hear you present the ideas in a “material” way that discusses the current trajectory of the project and introduces where you think its going from here and why. I expect a serious effort from the group to give each other commentary and to be tough and take notes. There is still time, but its getting close to the wire to make “radical” changes that some may need to make to kick start a new.

In the following two weeks everyone should focus on parts of their projects. Small scale first – then back to large scale. Ronny has a jump on this in how he has dealt with the ramp/circulation/stair/structure component of his project. His next step is to understand its incorporation into the large scale development of the site and how its modified or expanded to do this. We should all be at this stage after Friday.

RC

07 February 2011

Bernard Tschumi - Six Concepts Excerpt from Architecture and Disjunction

CONCEPT I: Technologies of Defamiliarization

In the mid-1970s small pockets of resistance began to form as architects in various parts of the world -- England, Austria, the United States, Japan (for the most part, in advanced postindustrial cultures) -- started to take advantage of this condition of fragmentation and superficiality and to turn it against itself. If the prevalent ideology was one of familiarity -- familiarity with known images, derived from 1920s modernism or eighteenth century classicism -- maybe one's role was to defamiliarize. If the new, mediated world echoed and reinforced our dismantled reality, maybe, just maybe, one should take advantage of such dismantling, celebrate fragmentation by celebrating the culture of differences, by accelerating and intensifying the loss of certainty, of center, of history.

In culture in general, the world of communication in the last twenty years has certainly helped the expression of a multiplicity of new “angles” on the canonic story, airing the views of women, immigrants, gays, minorities, and various non-Western identities who never sat comfortably within the supposed “community.” In architecture in particular, the notion of defamiliarization was a clear tool. If the design of windows only reflects the superficiality of the skin's decoration, we might very well start to look for a way to do without windows. If the design of pillars reflects the conventionality of a supporting frame, maybe we might get rid of pillars altogether.

Although the architects concerned might not profess an inclination towards the exploration of new technologies, such work usually took advantage of contemporary technological developments. Interestingly, the specific technologies -- air-conditioning or the construction of lightweight structures or computer modes of calculation -- have yet to be theorized in architectural culture. I stress this because other technological advances, such as the invention of the elevator or the nineteenth century development of steel construction, have been the subject of countless studies by historians, but very little such work exists in terms of contemporary technologies because these technologies do not necessarily produce historical forms.

I take this detour through technology because technology is inextricably linked to our contemporary condition: to say that society is now “about” media and mediation makes us aware that the direction taken by technology is less the domination of nature through technology than the development of information and the construction of the world as a set of “images.” Architects must again understand and take advantage of the use of such new technologies. In the words of the French writer, philosopher, and architect Paul Virilio,”we are not dealing anymore with the technology of construction, but with the construction of technology.”

CONCEPT II: The Mediated “Metropolitan” Shock

That constant flickering of images fascinates us, much as it fascinated Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. I hate to cite such a “classic,” but Gianni Vattimo's recent analyses of the text has indicated aspects that are illustrative of our contemporary condition. When Benjamin discussed the reproducibility of images, he pointed out that the loss of their exchange value, their “aura,” made them interchangeable, and that in an age of pure information the only thing that counted was the “shock” -- the shock of images, their surprise factor. This shock factor was what allowed an image to stand out: moreover, it was also characteristic of our contemporary condition, and of the dangers of life in the modern metropolis. These dangers resulted in constant anxiety about

finding oneself in a world in which everything was insignificant and gratuitous. The experience of such anxiety was an experience of defamiliarization, of un-zu-hause-sein, of unheimlichkeit, of the uncanny.

In many ways, the esthetic experience, according to Benjamin, consisted of keeping defamiliarization alive, as contrasted to its opposite -- familiarization, security, geborgenheit. I would like to point out that Benjamin's analysis corresponds exactly to the historical and philosophical dilemma of architecture. Is the experience of architecture something that is meant to defamiliarize -- let's say, a form of “art” -- or, on the contrary, is it something that is meant to be comforting, heimlich, homely: something that protects? Here, of course, one recognizes the constant opposition between those who see architecture and our cities as places of experience and experiment, as exciting reflections of contemporary society -- those who like “things that go bump in the night,” that “deconstruct and self-destruct” -- and those who see the role of architecture as refamiliarization, contextualization, insertion; in other words, those who describe themselves as historicists, contextualists, and postmodernists, since postmodernism in architecture now has a definitely classicist and historicist connotation.

The general public will almost always stand behind the traditionalists. In the public eye, architecture is about comfort, about shelter, about bricks and mortar. However, for those for whom architecture in not necessarily about comfort and geborgenheit , but is also about advancing society and its development, the device of shock may be an indispensable tool. Cities like New York, despite -- or maybe because of -- its homeless and two thousand murders a year become the post-industrial equivalent of Georg Simmel's preindustrial grosstadt that so fascinated and horrified Benjamin. Architecture in the megalopolis may be more about finding unfamiliar solutions to problems than about the quieting, comforting solutions of the establishment community.

Recently, we have seen important new research on cities in which the fragmentation and dislocation produced by the scaleless juxtaposition of highways, shopping centers, high-rise buildings, and small houses is seen as a positive sign of the vitality of urban culture. As opposed to nostalgic attempts to restore an impossible continuity of streets and plazas, this research implies making an event out of urban shock, intensifying and accelerating urban experience through clash and disjunction.

Let us return to the media. In our era of reproduction, we have seen how the conventional construction techniques of frame and skin corresponded to the superficiality and precariousness of media culture, and how a constant expansion of change was necessary to satisfy the often banal needs of the media. We have also seen that to endorse this logic means that any work is interchangeable with any other, just as we accelerate the shedding of the skin of a dormitory and replace it with another. We have also seen that the shock goes against the nostalgia of permanence or authority, whether it is in culture in general or architecture in particular. Over fifty years after the publication of Benjamin's text, we may have to say that shock is still all we have left to communicate in a time of generalized information. In a mediatized world, this relentless need for change is not necessarily to be understood as negative. The increase in change and superficiality also means a weakening of architecture as a form of domination, power, and authority, as it historically has been in the last six thousand years.

CONCEPT III: De-structuring

This “weakening” of architecture, this altered relationship between structure and image, structure and skin, is interesting to examine in the light of a debate that recently has resurfaced in architectural circles -- namely, structure

versus ornament. Since the Renaissance, architectural theory has always distinguished between structure and ornament, and has set forth the hierarchy between them. To quote Leon Battista Alberti: “Ornament has the character of something attached or additional.” Ornament is meant to be additive; it must not challenge or weaken the structure.

But what does this hierarchy mean today, when the structure often remains the same -- an endlessly repetitive and neutralized grid? In the majority of construction in this country today, structural practice is rigorously similar in concept: a basic frame of wood, steel, or concrete. As noted earlier, the decision whether to construct the frame from any of these materials is often left to the engineers and economists rather than to the architect. The architect is not meant to question structure. The structure must stand firm. After all, what would happen to insurance premiums (and to reputations) if the building collapsed? The result is too often a refusal to question structure. The structure must be stable, otherwise the edifice collapses -- the edifice, that is, both the building and the entire edifice of thought. For in comparison to science or philosophy, architecture rarely questions its foundations.

The result of these “habits of mind” in architecture is that the structure of a building is not supposed to be questioned anymore than are the mechanics of a projector when watching a movie, or the hardware of a television set when viewing images on its screen. Social critics regularly question the image, yet rarely question the apparatus, the frame. Still, for over a century, and especially in the past twenty years, we have seen the beginning of such questioning. Contemporary philosophy has touched upon this relationship between frame and image -- here the frame is seen as the structure, the armature, and the image as the ornament. Jacques Derrida's Parergon turns such questioning between frame and image into a theme. Although it might be argued that the frame of a painting does not quite equate to the frame of a building -- one being exterior or “hors d'oeuvre” and the other interior -- I would maintain that this is only a superficial objection. Traditionally, both frame and structure perform the same function of “holding it together.”

CONCEPT VI: Superimposition

This questioning of structure leads to a particular side of contemporary architectural debate, namely deconstruction. From the beginning, the polemics of deconstruction, together with much of post-structuralist thought, interested a small number of architects because it seemed to question the very principles of geborgenheit that the postmodernist mainstream was trying to promote. When I first met Jacques Derrida in order to try toconvince him to confront his own work with architecture, he asked me, “But how could an architect be interested in deconstruction? After all, deconstruction is anti-form, anti-hierarchy, anti-structure, the opposite of all that architecture stands for.” “Precisely for this reason,” I replied.

As years went by, the multiple interpretations that multiple architects gave to deconstruction became more multiple than deconstruction's theory of multiple readings could ever have hoped. For one architect it had to do with dissimulation, for another, with fragmentation; for yet another, with displacement. Again, to quote Nietzsche: “There are no facts, only an infinity of interpretations.” And very soon, maybe due to the fact that many architects shared the same dislike for the geborgenheit of the “historicist postmodernists” and the same fascination for the early twentieth century avant-garde, deconstructivism was born -- and immediately called a “style” -- precisely what these architects had been trying to avoid. Any interest in post-structuralist thought and deconstruction stemmed from the fact that they challenged the idea of a single unified set of images, the idea of certainty, and of course, the idea of an identifiable language.

Theoretical architects -- as they were called -- wanted to confront the binary oppostions of traditional architecture: namely form versus function, or abstraction versus figuration. However, they also wanted to challenge the implied hierarchies hidden in these dualities, such as, “form follows function,” and “ornament is subservient to structure.” This repudiation of hierarchy led to a fascination with complex images that were simultaneously “both” and “neither/nor” -- images that were the overlap or the superimposition of many other images. Superimposition became a key device. This can be seen in my own work. In The Manhattan Transcripts (1981) or The Screenplays (1977), the devices used in the first episodes were borrowed from film theory and the nouveau roman. In the Transcripts the distinction between structure (or frame), form (or space), event (or function), body (or movement), and fiction (or narrative) was systematically blurred through superimposition, collision, distortion, fragmentation, and so forth. We find superimposition used quite remarkably in Peter Eisenman's work, where the overlays for his Romeo and Juliet project pushed literary and philosophical parallels to extremes. These different realities challenged any single interpretation, constantly trying to problematize the architectural object, crossing boundaries between film literature, and architecture (“Was it a play or was it a piece of architecture?”).

Much of this work benefited from the environment of the universities and the art scene -- its galleries and publications -- where the crossover among different fields allowed architects to blur the distinctions between genres, constantly questioning the discipline of architecture and its hierarchies of form. Yet if I was to examine both my own work of this time and that of my colleagues, I would say that both grew out of a critique of architecture, of the nature of architecture. It dismantled concepts and became a remarkable conceptual tool, but it could not address the one thing that makes the work of architects ultimately different from the work of philosophers: materiality.

Just as there is a logic of words or of drawings, there is a logic of materials, and they are not the same. And however much they are subverted, something ultimately resists. Ceci n'est pas une pipe. A word is not a concrete block. The concept of dog does not bark. To quote Gilles Deleuze, “The concepts of film are not given in film.” When metaphors and catachreses are turned into buildings, they generally turn into plywood or papier mâché stage sets: the ornament again. Sheetrock columns that do not touch the ground are not structural, they are ornament. Yes, fiction and narrative fascinated many architects, perhaps because, our enemies might say, we knew more about books than about buildings.

I do not have the time to dwell upon an interesting difference between the two interpretations of the role of fiction in architecture; one, the so-called “historicist postmodernist” allegiance, the other, the so-called “deconstructivist neo-modernist” allegiance (not my labels). Although both stemmed from early interests in linguistics and semiology, the first group saw fiction and narrative as part of the realm of metaphors, of a new architecture parlante, of form, while the second group saw fiction and scenarios as analogues for programs and function.

I would like to concentrate on that second view. Rather than manipulating the formal properties of architecture, we might look into what really happens inside buildings and cities: the function, the program, the properly historical dimension of architecture. Roland Barthes' Structural Analysis of Narratives was fascinating in this respect, for it could be directly transposed both in spatial and programmatic sequence. The same could be said of much of Sergei Eisenstein's theory of film montage.

CONCEPT V: Crossprogramming

Architecture has always been as much about the event that takes place in a space as about the space itself. The Columbia University Rotunda has been a library, it has been used as a banquet hall, it is often the site of university lectures; someday it could fulfill the needs for an athletic facility at the University. What a wonderful swimming pool the Rotunda would be! You may think I'm being facetious, but in today's world where railway stations become museums and churches become nightclubs, a point is being made: the complete interchangeability of form and function, the loss of traditional, canonic cause-and-effect relationships as sanctified by modernism. Function does not follow form, form does not follow function -- or fiction for that matter -- however, they certainly interact. Diving into this great blue Rotonda pool -- a part of the shock.

If shock can no longer be produced by the succession and juxtaposition of facades and lobbies, maybe it can be produced by the juxtaposition of events that take place behind these facades in these spaces. If “the respective contamination of all categories, the constant substitutions, the confusion of genres” -- as described by critics of the right and left alike from Andreas Huyssens to Jean Baudrillard -- is the new direction of our times, it may well be used to one's advantage, to the advantage of a general rejuvenation of architecture. If architecture is both concept and experience, space and use, structure and superficial image -- non-hierarchically -- then architecture should cease to separate these categories and instead merge them into unprecedented combinations of programs and spaces. “Crossprogramming,” “transprogramming,” “disprogramming:” I have elaborated on these concepts elsewhere, suggesting the displacement and mutual contamination of terms.

CONCEPT VI: Events: The Turning Point

My own work in the 1970s constantly reiterated that there was no architecture without event, no architecture without action, without activities, without functions. Architecture was seen as the combination of spaces, events, and movements without any hierarchy or precedence among these concepts. The hierarchical cause-and-effect relationship between function and form is one of the great certainties of architectural thinking -- the one that lies behind that reassuring ideé recue of community life that tells us that we live in houses “designed to answer to our needs,” or in cities planned as machines to live in. Geborgenheit connotations of this notion go against both the real “pleasure” of architecture, in its unexpected combinations of terms, and the reality of contemporary urban life in its most stimulative, unsettling directions. Hence, in works like The Manhattan Transcripts, the definition of architecture could not be form or walls, but had to be the combination of heterogeneous and incompatible terms.

The insertion of the terms “event” and “movement” was influenced by Situationist discourse and by the `68 era. Les événements, as they were called, were not only “events” in action, but also in thought. Erecting a barricade (function) in a Paris street (form) is not quite equivalent to being a flaneur (function) in that same street (form). Dining (function) in the Rotunda (form) is not quite equivalent to reading or swimming in it. Here all hierarchical relationships between form and function cease to exist. This unlikely combination of events and spaces was charged with subversive capabilities, for it challenged both the function and the space. Such confrontation parallels the Surrealists' meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table, or closer to us, Rem Koolhaas's description of the Downtown Athletic Club: “Eating oysters with boxing gloves, naked, on the nth floor.”

We find it today in Tokyo, with multiple programs scattered throughout the floors of high-rise buildings: a department store, a museum, a health club, and a railway station, with putting greens on the roof. And we will find it in the

programs of the future, where airports are simultaneously amusement arcades, athletic facilities, cinemas, and so on. Regardless of whether they are the result of chance combinations, or are due to the pressure of ever-rising land prices, such non-causal relationships between form and function, or space and action go beyond poetic confrontations of unlikely bedfellows. Michel Foucault, as recently cited in an excellent book by John Rajchman, expanded the use of the term “event” in a manner that went beyond the single action or activity, and spoke of “events of thought.” For Foucault, an event is not simply a logical sequence of words or actions, but rather “the moment of erosion, collapse, questioning, or problematization of the very assumptions of the setting within which a drama may take place -- occasioning the chance or possibility of another, different setting.” The event here is seen as a turning point -- not an origin or an end -- as opposed to such propositions as “form follows function.” I would like to propose that the future of architecture lies in the construction of such events.

Just as important is the spatialization that goes with the event. Such a concept is quite different from the project of the modern movement, which sought the affirmation of certainties in a unified utopia as opposed to our current questioning of multiple, fragmented, dislocated terrains.

A few years later, in an essay about the follies of the Parc de la Villette, Jacques Derrida expanded on the definition of event, calling it “the emergence of a disparate multiplicity.” I had constantly insisted, in our discussions and elsewhere, that these points called folies were points of activities, of programs, of events. Derrida elaborated on this concept, proposing the possibility of an “architecture of the event” that would “eventualize,” or open up that which, in our history or tradition, is understood to be fixed, essential, monumental. He had also suggested earlier that the word “event” shared roots with “invention,” hence the notion of the event, of the action-in-space, of the turning point, the invention. I would like to associate it with the notion of shock, a shock that in order to be effective in our mediated culture, in our culture of images, must go beyond Walter Benjamin's definition and combine the idea of function or action with that of image. Indeed, architecture finds itself in a unique situation: it is the only discipline that by definition combines concept and experience, image and use, image and structure. Philosophers can write, mathematicians can develop virtual spaces, but architects are the only ones who are the prisoners of that hybrid art, where the image hardly ever exists without a combined activity.

It is my contention that far from being a field suffering from the incapability of questioning its structures and foundations, it is the field where the greatest discoveries will take place in the next century. The very heterogeneity of the definition of architecture -- space, action, and movement -- makes it into that event, that place of shock, or that place of the invention of ourselves. The event is the place where the rethinking and reformulation of the different elements of architecture, many of which have resulted in or added to contemporary social inequities, may lead to their solution. By definition, it is the place of the combination of differences.

This will not happen by imitating the past and eighteenth century ornaments. It also will not happen by simply commenting, through design, on the various dislocations and uncertainties of our contemporary condition. I do not believe it is possible, nor does it make sense, to design buildings that formally attempt to blur traditional structures, that is, that display forms that lie somewhere between abstraction and figuration, or between structure and ornament, or that are cut-up and dislocated for esthetic reasons. Architecture is not an illustrative art; it does not illustrate theories. (I do not believe you can design deconstruction.) You cannot design a new definition of cities and their architecture. But one may be able to design the conditions that will make it possible for this non-hierarchical, non-

traditional society to happen. By understanding the nature of our contemporary circumstances and the media processes that accompany them, architects possess the possibility of constructing conditions that will create a new city and new relationships between spaces and events.

Architecture is not about the conditions of design, but about the design of conditions that will dislocate the most traditional and regressive aspects of our society and simultaneously reorganize these elements in the most liberating way, where our experience becomes the experience of events organized and strategized through architecture. Strategy is a key word in architecture today. No more masterplans, no more locating in a fixed place, but a new heterotopia. This is what our cities must strive towards and what we architects must help them to achieve by intensifying the rich collision of events and spaces. Tokyo and New York only appear chaotic. Instead, they mark the appearance of a new urban structure, a new urbanity. Their confrontations and combinations of elements may provide us with the event, the shock, that I hope will make the architecture of our cities a turning point in culture and society.

In the mid-1970s small pockets of resistance began to form as architects in various parts of the world -- England, Austria, the United States, Japan (for the most part, in advanced postindustrial cultures) -- started to take advantage of this condition of fragmentation and superficiality and to turn it against itself. If the prevalent ideology was one of familiarity -- familiarity with known images, derived from 1920s modernism or eighteenth century classicism -- maybe one's role was to defamiliarize. If the new, mediated world echoed and reinforced our dismantled reality, maybe, just maybe, one should take advantage of such dismantling, celebrate fragmentation by celebrating the culture of differences, by accelerating and intensifying the loss of certainty, of center, of history.

In culture in general, the world of communication in the last twenty years has certainly helped the expression of a multiplicity of new “angles” on the canonic story, airing the views of women, immigrants, gays, minorities, and various non-Western identities who never sat comfortably within the supposed “community.” In architecture in particular, the notion of defamiliarization was a clear tool. If the design of windows only reflects the superficiality of the skin's decoration, we might very well start to look for a way to do without windows. If the design of pillars reflects the conventionality of a supporting frame, maybe we might get rid of pillars altogether.

Although the architects concerned might not profess an inclination towards the exploration of new technologies, such work usually took advantage of contemporary technological developments. Interestingly, the specific technologies -- air-conditioning or the construction of lightweight structures or computer modes of calculation -- have yet to be theorized in architectural culture. I stress this because other technological advances, such as the invention of the elevator or the nineteenth century development of steel construction, have been the subject of countless studies by historians, but very little such work exists in terms of contemporary technologies because these technologies do not necessarily produce historical forms.

I take this detour through technology because technology is inextricably linked to our contemporary condition: to say that society is now “about” media and mediation makes us aware that the direction taken by technology is less the domination of nature through technology than the development of information and the construction of the world as a set of “images.” Architects must again understand and take advantage of the use of such new technologies. In the words of the French writer, philosopher, and architect Paul Virilio,”we are not dealing anymore with the technology of construction, but with the construction of technology.”

CONCEPT II: The Mediated “Metropolitan” Shock

That constant flickering of images fascinates us, much as it fascinated Walter Benjamin in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. I hate to cite such a “classic,” but Gianni Vattimo's recent analyses of the text has indicated aspects that are illustrative of our contemporary condition. When Benjamin discussed the reproducibility of images, he pointed out that the loss of their exchange value, their “aura,” made them interchangeable, and that in an age of pure information the only thing that counted was the “shock” -- the shock of images, their surprise factor. This shock factor was what allowed an image to stand out: moreover, it was also characteristic of our contemporary condition, and of the dangers of life in the modern metropolis. These dangers resulted in constant anxiety about

finding oneself in a world in which everything was insignificant and gratuitous. The experience of such anxiety was an experience of defamiliarization, of un-zu-hause-sein, of unheimlichkeit, of the uncanny.

In many ways, the esthetic experience, according to Benjamin, consisted of keeping defamiliarization alive, as contrasted to its opposite -- familiarization, security, geborgenheit. I would like to point out that Benjamin's analysis corresponds exactly to the historical and philosophical dilemma of architecture. Is the experience of architecture something that is meant to defamiliarize -- let's say, a form of “art” -- or, on the contrary, is it something that is meant to be comforting, heimlich, homely: something that protects? Here, of course, one recognizes the constant opposition between those who see architecture and our cities as places of experience and experiment, as exciting reflections of contemporary society -- those who like “things that go bump in the night,” that “deconstruct and self-destruct” -- and those who see the role of architecture as refamiliarization, contextualization, insertion; in other words, those who describe themselves as historicists, contextualists, and postmodernists, since postmodernism in architecture now has a definitely classicist and historicist connotation.

The general public will almost always stand behind the traditionalists. In the public eye, architecture is about comfort, about shelter, about bricks and mortar. However, for those for whom architecture in not necessarily about comfort and geborgenheit , but is also about advancing society and its development, the device of shock may be an indispensable tool. Cities like New York, despite -- or maybe because of -- its homeless and two thousand murders a year become the post-industrial equivalent of Georg Simmel's preindustrial grosstadt that so fascinated and horrified Benjamin. Architecture in the megalopolis may be more about finding unfamiliar solutions to problems than about the quieting, comforting solutions of the establishment community.

Recently, we have seen important new research on cities in which the fragmentation and dislocation produced by the scaleless juxtaposition of highways, shopping centers, high-rise buildings, and small houses is seen as a positive sign of the vitality of urban culture. As opposed to nostalgic attempts to restore an impossible continuity of streets and plazas, this research implies making an event out of urban shock, intensifying and accelerating urban experience through clash and disjunction.

Let us return to the media. In our era of reproduction, we have seen how the conventional construction techniques of frame and skin corresponded to the superficiality and precariousness of media culture, and how a constant expansion of change was necessary to satisfy the often banal needs of the media. We have also seen that to endorse this logic means that any work is interchangeable with any other, just as we accelerate the shedding of the skin of a dormitory and replace it with another. We have also seen that the shock goes against the nostalgia of permanence or authority, whether it is in culture in general or architecture in particular. Over fifty years after the publication of Benjamin's text, we may have to say that shock is still all we have left to communicate in a time of generalized information. In a mediatized world, this relentless need for change is not necessarily to be understood as negative. The increase in change and superficiality also means a weakening of architecture as a form of domination, power, and authority, as it historically has been in the last six thousand years.

CONCEPT III: De-structuring

This “weakening” of architecture, this altered relationship between structure and image, structure and skin, is interesting to examine in the light of a debate that recently has resurfaced in architectural circles -- namely, structure

versus ornament. Since the Renaissance, architectural theory has always distinguished between structure and ornament, and has set forth the hierarchy between them. To quote Leon Battista Alberti: “Ornament has the character of something attached or additional.” Ornament is meant to be additive; it must not challenge or weaken the structure.

But what does this hierarchy mean today, when the structure often remains the same -- an endlessly repetitive and neutralized grid? In the majority of construction in this country today, structural practice is rigorously similar in concept: a basic frame of wood, steel, or concrete. As noted earlier, the decision whether to construct the frame from any of these materials is often left to the engineers and economists rather than to the architect. The architect is not meant to question structure. The structure must stand firm. After all, what would happen to insurance premiums (and to reputations) if the building collapsed? The result is too often a refusal to question structure. The structure must be stable, otherwise the edifice collapses -- the edifice, that is, both the building and the entire edifice of thought. For in comparison to science or philosophy, architecture rarely questions its foundations.

The result of these “habits of mind” in architecture is that the structure of a building is not supposed to be questioned anymore than are the mechanics of a projector when watching a movie, or the hardware of a television set when viewing images on its screen. Social critics regularly question the image, yet rarely question the apparatus, the frame. Still, for over a century, and especially in the past twenty years, we have seen the beginning of such questioning. Contemporary philosophy has touched upon this relationship between frame and image -- here the frame is seen as the structure, the armature, and the image as the ornament. Jacques Derrida's Parergon turns such questioning between frame and image into a theme. Although it might be argued that the frame of a painting does not quite equate to the frame of a building -- one being exterior or “hors d'oeuvre” and the other interior -- I would maintain that this is only a superficial objection. Traditionally, both frame and structure perform the same function of “holding it together.”

CONCEPT VI: Superimposition

This questioning of structure leads to a particular side of contemporary architectural debate, namely deconstruction. From the beginning, the polemics of deconstruction, together with much of post-structuralist thought, interested a small number of architects because it seemed to question the very principles of geborgenheit that the postmodernist mainstream was trying to promote. When I first met Jacques Derrida in order to try toconvince him to confront his own work with architecture, he asked me, “But how could an architect be interested in deconstruction? After all, deconstruction is anti-form, anti-hierarchy, anti-structure, the opposite of all that architecture stands for.” “Precisely for this reason,” I replied.

As years went by, the multiple interpretations that multiple architects gave to deconstruction became more multiple than deconstruction's theory of multiple readings could ever have hoped. For one architect it had to do with dissimulation, for another, with fragmentation; for yet another, with displacement. Again, to quote Nietzsche: “There are no facts, only an infinity of interpretations.” And very soon, maybe due to the fact that many architects shared the same dislike for the geborgenheit of the “historicist postmodernists” and the same fascination for the early twentieth century avant-garde, deconstructivism was born -- and immediately called a “style” -- precisely what these architects had been trying to avoid. Any interest in post-structuralist thought and deconstruction stemmed from the fact that they challenged the idea of a single unified set of images, the idea of certainty, and of course, the idea of an identifiable language.

Theoretical architects -- as they were called -- wanted to confront the binary oppostions of traditional architecture: namely form versus function, or abstraction versus figuration. However, they also wanted to challenge the implied hierarchies hidden in these dualities, such as, “form follows function,” and “ornament is subservient to structure.” This repudiation of hierarchy led to a fascination with complex images that were simultaneously “both” and “neither/nor” -- images that were the overlap or the superimposition of many other images. Superimposition became a key device. This can be seen in my own work. In The Manhattan Transcripts (1981) or The Screenplays (1977), the devices used in the first episodes were borrowed from film theory and the nouveau roman. In the Transcripts the distinction between structure (or frame), form (or space), event (or function), body (or movement), and fiction (or narrative) was systematically blurred through superimposition, collision, distortion, fragmentation, and so forth. We find superimposition used quite remarkably in Peter Eisenman's work, where the overlays for his Romeo and Juliet project pushed literary and philosophical parallels to extremes. These different realities challenged any single interpretation, constantly trying to problematize the architectural object, crossing boundaries between film literature, and architecture (“Was it a play or was it a piece of architecture?”).

Much of this work benefited from the environment of the universities and the art scene -- its galleries and publications -- where the crossover among different fields allowed architects to blur the distinctions between genres, constantly questioning the discipline of architecture and its hierarchies of form. Yet if I was to examine both my own work of this time and that of my colleagues, I would say that both grew out of a critique of architecture, of the nature of architecture. It dismantled concepts and became a remarkable conceptual tool, but it could not address the one thing that makes the work of architects ultimately different from the work of philosophers: materiality.

Just as there is a logic of words or of drawings, there is a logic of materials, and they are not the same. And however much they are subverted, something ultimately resists. Ceci n'est pas une pipe. A word is not a concrete block. The concept of dog does not bark. To quote Gilles Deleuze, “The concepts of film are not given in film.” When metaphors and catachreses are turned into buildings, they generally turn into plywood or papier mâché stage sets: the ornament again. Sheetrock columns that do not touch the ground are not structural, they are ornament. Yes, fiction and narrative fascinated many architects, perhaps because, our enemies might say, we knew more about books than about buildings.

I do not have the time to dwell upon an interesting difference between the two interpretations of the role of fiction in architecture; one, the so-called “historicist postmodernist” allegiance, the other, the so-called “deconstructivist neo-modernist” allegiance (not my labels). Although both stemmed from early interests in linguistics and semiology, the first group saw fiction and narrative as part of the realm of metaphors, of a new architecture parlante, of form, while the second group saw fiction and scenarios as analogues for programs and function.

I would like to concentrate on that second view. Rather than manipulating the formal properties of architecture, we might look into what really happens inside buildings and cities: the function, the program, the properly historical dimension of architecture. Roland Barthes' Structural Analysis of Narratives was fascinating in this respect, for it could be directly transposed both in spatial and programmatic sequence. The same could be said of much of Sergei Eisenstein's theory of film montage.

CONCEPT V: Crossprogramming

Architecture has always been as much about the event that takes place in a space as about the space itself. The Columbia University Rotunda has been a library, it has been used as a banquet hall, it is often the site of university lectures; someday it could fulfill the needs for an athletic facility at the University. What a wonderful swimming pool the Rotunda would be! You may think I'm being facetious, but in today's world where railway stations become museums and churches become nightclubs, a point is being made: the complete interchangeability of form and function, the loss of traditional, canonic cause-and-effect relationships as sanctified by modernism. Function does not follow form, form does not follow function -- or fiction for that matter -- however, they certainly interact. Diving into this great blue Rotonda pool -- a part of the shock.

If shock can no longer be produced by the succession and juxtaposition of facades and lobbies, maybe it can be produced by the juxtaposition of events that take place behind these facades in these spaces. If “the respective contamination of all categories, the constant substitutions, the confusion of genres” -- as described by critics of the right and left alike from Andreas Huyssens to Jean Baudrillard -- is the new direction of our times, it may well be used to one's advantage, to the advantage of a general rejuvenation of architecture. If architecture is both concept and experience, space and use, structure and superficial image -- non-hierarchically -- then architecture should cease to separate these categories and instead merge them into unprecedented combinations of programs and spaces. “Crossprogramming,” “transprogramming,” “disprogramming:” I have elaborated on these concepts elsewhere, suggesting the displacement and mutual contamination of terms.

CONCEPT VI: Events: The Turning Point

My own work in the 1970s constantly reiterated that there was no architecture without event, no architecture without action, without activities, without functions. Architecture was seen as the combination of spaces, events, and movements without any hierarchy or precedence among these concepts. The hierarchical cause-and-effect relationship between function and form is one of the great certainties of architectural thinking -- the one that lies behind that reassuring ideé recue of community life that tells us that we live in houses “designed to answer to our needs,” or in cities planned as machines to live in. Geborgenheit connotations of this notion go against both the real “pleasure” of architecture, in its unexpected combinations of terms, and the reality of contemporary urban life in its most stimulative, unsettling directions. Hence, in works like The Manhattan Transcripts, the definition of architecture could not be form or walls, but had to be the combination of heterogeneous and incompatible terms.

The insertion of the terms “event” and “movement” was influenced by Situationist discourse and by the `68 era. Les événements, as they were called, were not only “events” in action, but also in thought. Erecting a barricade (function) in a Paris street (form) is not quite equivalent to being a flaneur (function) in that same street (form). Dining (function) in the Rotunda (form) is not quite equivalent to reading or swimming in it. Here all hierarchical relationships between form and function cease to exist. This unlikely combination of events and spaces was charged with subversive capabilities, for it challenged both the function and the space. Such confrontation parallels the Surrealists' meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table, or closer to us, Rem Koolhaas's description of the Downtown Athletic Club: “Eating oysters with boxing gloves, naked, on the nth floor.”

We find it today in Tokyo, with multiple programs scattered throughout the floors of high-rise buildings: a department store, a museum, a health club, and a railway station, with putting greens on the roof. And we will find it in the

programs of the future, where airports are simultaneously amusement arcades, athletic facilities, cinemas, and so on. Regardless of whether they are the result of chance combinations, or are due to the pressure of ever-rising land prices, such non-causal relationships between form and function, or space and action go beyond poetic confrontations of unlikely bedfellows. Michel Foucault, as recently cited in an excellent book by John Rajchman, expanded the use of the term “event” in a manner that went beyond the single action or activity, and spoke of “events of thought.” For Foucault, an event is not simply a logical sequence of words or actions, but rather “the moment of erosion, collapse, questioning, or problematization of the very assumptions of the setting within which a drama may take place -- occasioning the chance or possibility of another, different setting.” The event here is seen as a turning point -- not an origin or an end -- as opposed to such propositions as “form follows function.” I would like to propose that the future of architecture lies in the construction of such events.

Just as important is the spatialization that goes with the event. Such a concept is quite different from the project of the modern movement, which sought the affirmation of certainties in a unified utopia as opposed to our current questioning of multiple, fragmented, dislocated terrains.

A few years later, in an essay about the follies of the Parc de la Villette, Jacques Derrida expanded on the definition of event, calling it “the emergence of a disparate multiplicity.” I had constantly insisted, in our discussions and elsewhere, that these points called folies were points of activities, of programs, of events. Derrida elaborated on this concept, proposing the possibility of an “architecture of the event” that would “eventualize,” or open up that which, in our history or tradition, is understood to be fixed, essential, monumental. He had also suggested earlier that the word “event” shared roots with “invention,” hence the notion of the event, of the action-in-space, of the turning point, the invention. I would like to associate it with the notion of shock, a shock that in order to be effective in our mediated culture, in our culture of images, must go beyond Walter Benjamin's definition and combine the idea of function or action with that of image. Indeed, architecture finds itself in a unique situation: it is the only discipline that by definition combines concept and experience, image and use, image and structure. Philosophers can write, mathematicians can develop virtual spaces, but architects are the only ones who are the prisoners of that hybrid art, where the image hardly ever exists without a combined activity.

It is my contention that far from being a field suffering from the incapability of questioning its structures and foundations, it is the field where the greatest discoveries will take place in the next century. The very heterogeneity of the definition of architecture -- space, action, and movement -- makes it into that event, that place of shock, or that place of the invention of ourselves. The event is the place where the rethinking and reformulation of the different elements of architecture, many of which have resulted in or added to contemporary social inequities, may lead to their solution. By definition, it is the place of the combination of differences.

This will not happen by imitating the past and eighteenth century ornaments. It also will not happen by simply commenting, through design, on the various dislocations and uncertainties of our contemporary condition. I do not believe it is possible, nor does it make sense, to design buildings that formally attempt to blur traditional structures, that is, that display forms that lie somewhere between abstraction and figuration, or between structure and ornament, or that are cut-up and dislocated for esthetic reasons. Architecture is not an illustrative art; it does not illustrate theories. (I do not believe you can design deconstruction.) You cannot design a new definition of cities and their architecture. But one may be able to design the conditions that will make it possible for this non-hierarchical, non-

traditional society to happen. By understanding the nature of our contemporary circumstances and the media processes that accompany them, architects possess the possibility of constructing conditions that will create a new city and new relationships between spaces and events.

Architecture is not about the conditions of design, but about the design of conditions that will dislocate the most traditional and regressive aspects of our society and simultaneously reorganize these elements in the most liberating way, where our experience becomes the experience of events organized and strategized through architecture. Strategy is a key word in architecture today. No more masterplans, no more locating in a fixed place, but a new heterotopia. This is what our cities must strive towards and what we architects must help them to achieve by intensifying the rich collision of events and spaces. Tokyo and New York only appear chaotic. Instead, they mark the appearance of a new urban structure, a new urbanity. Their confrontations and combinations of elements may provide us with the event, the shock, that I hope will make the architecture of our cities a turning point in culture and society.

In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

"And so it has come to be that the beauty of a Japanese room depends on the variation of shadows, heavy shadows against light shadows—it has nothing else. Westerners are amazed at the simplicity of Japanese rooms, perceiving in them no more than ashen walls bereft of ornament. Their reaction is understandable, but it betrays a failure to comprehend the mystery of shadows. Out beyond the sitting room, which the rays of the sun at best can but barely reach, we extend the eaves or build a veranda, putting the sunlight at still greater a remove. The light from the garden steals in but dimly through paper-paneled doors, and it is precisely this indirect light that makes for us the charm of the room. We do our walls in neutral colors so that the sad, fragile, dying rays can sink into absolute repose. The storehouse, kitchen, hallways, and such may have a glossy finish, but the walls of the sitting room will almost always be of clay textured with fine sand. A luster here would destroy the soft fragile beauty of the feeble light. We delight in the mere sight of the delicate glow of fading rays clinging to the surface of a dusky wall, there to live out what little life remains to them. We never tire of the sight, for to us this pale glow and these dim shadows far surpass any ornament…"

06 February 2011

Reminder

Books and Walk-Through Boards are due no later than 2/8.

02 February 2011

Schedule (revised)

Design 8 – 02/01/11

As a rule – Tuesdays will be individual review and Fridays are for group reviews and Pin-up. The below schedule is a guide and may change as the semester progresses, but the content is expected to be delivered by these dates. More thinking and analysis in the first half and more production in the second half, but quality and quantity is expected to be the same throughout.

The main topics of conversation will be:

Material

Analysis

Sustainability

Plan and Program

Expectations:

Self-Motivation

Quality craft and analysis

Complete presentation and continuous development at multiple scales

Jan 25

Jan 28 Begin Material and Programming Study.

What is this thing made of? What is its structure? And why?

Feb 1

Feb 4 Group review. Where are we at.

Feb 8 Student Pecha Kucha – 1245-200pm each campus.

Study of Analysis – Joint review with Amoia Studio

Uncover similar designs and structures for presentation.

Final deadline for Book printing.

Feb 11 Pin-Up - Complete Material Study. Start “small scale” design study.

Present the material possibilities and explain their relation to concept, structure and site. Discuss the sustainable aspects of selections. How do they relate to the context of the site and to the context of your idea.

Feb 15

Feb 18 Pin-Up - Compete “small scale” design study. Begin its application of into large scale

Complete the focused analysis and explain its application in your project. Determine what needs further study and begin that analysis.

Feb 22

Feb 25 Group review of precedent analysis, material and site. Present programming studies.

Program the plan and the material into a site. Outline the Sustainable Design strategies and diagram them. Begin to model the building into its site. Use physical model to discuss program intentions and site relations. Use a digital model to show interaction of views and material.

Mar 1

Mar 4 Plan, section, site presentation. Re-Write thesis statement preview of Mid-term reviews.

By this date we MUST see a complete set of schematic plans, sections and site relationship diagrams. This presentation is a “warm-up” for the mid-term and MUST contain everything you intent to present.

Mar 8 Mid-term reviews

Mar 11 NAAB Mid-term reviews

Mar 15 NAAB Mid-term reviews

Mar 18 Mid-term reviews

Mar 22 Spring Break

Mar 25 Spring Break

Mar 29

Apr 1 Pin-Up – Review of changes. Complete presentation of planning programming and site.

Respond to Mid-Term criticism and re-present.

Apr 5

Apr 8 Group review of complete plan, section, site presentation.

Apr 12

Apr 15 Pin-Up – First complete project review with complete model and 3D analysis. Material and “small scale” studies reincorporated.

We will have a guest critic TBA.

Apr 19

Apr 22 Group review. Time is running out.

Apr 26